It’s December 1943 in Rome. Nino is in danger but help can arrive in unexpected ways …

‘I love you, sweetheart.’ Nino ruffled Carla’s dark curls.

They both knew the next phrase, a part of their ritual: “Be a good girl, look after Mama” … but no longer. Two pairs of blue eyes met, begging each other not to cry.

‘Signora Pagano’s here and I’ll come back soon.’ Nino had stayed too long and their neighbour hovered nervously by the door. ‘Bye my darling.’ He kissed Carla and turned, as Berti bounded behind him. A mass of pale fur, the dog was Carla’s adopted friend; Nino hoped that Signora Pagano would cope with them both.

The elderly lady squeezed his hand. ‘Be careful and see you soon.’ She restrained Berti as Nino hurried outside.

The December air was cold but Nino felt hot, beginning to panic. The curfew began at five and he had to leave Rome before then.

‘Papa!’

Nino turned to see Carla in the doorway, holding up his violin case. Not this time. He shook his head and blew her a kiss.

Familiar faces watched and their expressions were dulled with sympathy. ‘They won’t report me,’ he murmured but took the next turning, picking up his pace. He mapped the route in his head, enough twists and turns to avoid being followed: a small street to his right and the next to his left.

Strangers passed him, racing against the cold and curfew. A few travelled his way but only for a road or two … and yet he felt that someone was following.

Nino thought quickly and turned towards the Opera House. The stage door was unmanned, so the doorman must be inside: good. He took the steps to the basement and nestled in the stairwell, where he was invisible from the road. His pursuer would probably pass by but, otherwise, Nino could slip inside. This basement door was never locked.

Footsteps and a muffled sound came closer, then stopped. Nino reached for the door handle but Berti bounded down and enthusiastically licked his hands. Carla followed.

‘I’ve brought your violin.’

‘Why?’

‘Playing it makes you smile.’

He had tried all day to be strong but Carla’s words shattered his resolve. Tears flowed down his cheeks and Berti tried to lick them away.

Carla hugged them both.

‘Papa, you’ve got us,’ she murmured.

Nino edged away, shaking his head. ‘Sweetheart, I have to go.’

‘No, Papa, we have to go.’

Berti licked Nino’s hand, in agreement.

‘But it’s dangerous.’

‘So’s staying in Rome.’

Nino tried to think. Carla could stay with him and the partisans for a day or two and then return to Rome. ‘Alright, but someone may have told the authorities I’m in Rome. If there’s any sign of danger, run away and go home. Alright?’

Carla’s head moved, although it might have been a nod or a shake.

They hurried away from the Opera House, Nino holding his violin case and clutching Carla’s hand. Berti trotted alongside, matching them step for step. Suddenly, two policemen emerged from a side street and turned towards them. Nino flinched.

‘Relax, Papa,’ Carla whispered. ‘No partisan wanders through Rome with his daughter, dog and violin …’

Nino tried to smile.

The older policeman acknowledged Nino with a friendly nod.

‘My daughter used to meet me from work,’ they heard him tell his colleague.

Carla squeezed Nino’s hand.

They were making good progress, taking the smaller streets, when they heard a whistle followed by shouts:

‘I saw him – that way!’

Nino hoped they meant someone else but booted footsteps were running … closer.

‘Go!’

Carla guided Berti into a small alley. Nino heard the dog whine in protest but at least they were safe. He raced to the junction and turned left. Two shots rang out and he felt the impact as the second ricocheted from the violin case.

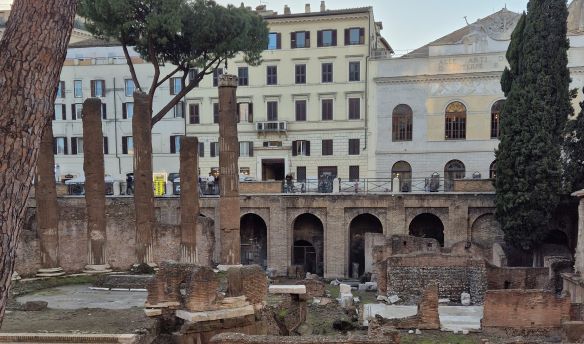

Nino kept running and the boots became muted and distant. Close to the Pantheon were narrow roads, with doorways for shelter and no dead ends. That was where he was going.

**************************************************************************

Nino paused in a shadowy doorway, trying to think. It was too late to leave Rome tonight: I’ll have to hide and leave tomorrow. He leant against the wooden arch and realised that he was shaking.

Minutes later, he heard footsteps close to the Pantheon. Was it a routine patrol or were they looking for him? The footfall moved into the narrow road parallel to Nino’s. He left the doorway and crept further along, ready to turn into the next road if they entered this one. His feet and hands were numb and he shifted the violin from his left to right hand, feeling the edge of the case. It was dented not broken and the violin would be fine: lucky they didn’t hit me.

I can’t do this all night. He had to find somewhere to stay. There was a place he knew close to the Lungotevere and, once the footsteps left, he would go there.

They were coming his way again and Nino entered the next road just in time.

It felt like hours but finally Nino heard a German command and the boots marched west. I’ll wait ten minutes and then I’ll leave.

**************************************************************************

Carla heard the soldiers too. ‘Come on, Berti,’ she whispered. They raced alongside the curved Pantheon walls and darted into the small road on their right. Carla crouched stroking the dog, who whimpered quietly. ‘You picked up Papa’s scent, didn’t you? We’ll go back when we’re sure the soldiers have gone.’

Berti lay down and Carla looked out from her vantage point. Her eyes had adjusted to the dark and she had an excellent view of Piazza della Minerva. The marble elephant stood on a plinth in the centre, its trunk angled towards her, as if in welcome.

Berti stood, suddenly alert, and Carla heard someone race by the Pantheon: it was Nino. She wanted to call out and Berti strained as she held his collar but other footsteps sounded, approaching the far end of the Piazza. Nino dived behind the elephant’s plinth.

Two soldiers entered the Piazza and paused. They can’t see Papa from there. One pointed a torch around the edges of the Piazza and then on the elephant.

Carla told herself it was a trick of the light, but the elephant’s trunk seemed to move. The soldiers must have seen it too. One gasped, edging back, and Carla knew enough German to understand: “Let’s go”. The other soldier flashed his torch again and this time the trunk swung towards him. Carla heard the torch fall on the flagstones.

At that moment, Nino lost his balance. He was still hidden but Carla heard him fall. So did the soldiers.

One soldier picked up the torch but it no longer worked. His companion was immobile.

Carla thought quickly: they’re unnerved already, one more fright and they’ll go. She wrapped her shawl around Berti’s body and coaxed him into the Piazza. From a distance, only his light-coloured head would be visible.

‘Sit, Berti,’ she whispered.

Now Carla began to sing the German carol she had learnt years before:

Stille Nacht, heilige Nacht (Silent night, holy hight)

Alles schläft; einsam wacht

Nur das traute hochheilige Paar.

Holder Knabe im lockingen Haar …

A moving elephant statue and a singing dog’s head. The soldiers had had enough and beat a hasty retreat.

Carla stopped singing and removed the shawl from Berti. ‘Well done!’

Nino raced over to join them. ‘Thank you! Let’s get out of here: there’s a place near the Lungotevere.’

**************************************************************************

The shadowy plane trees beside the river resembled a line of silent sentries. Carla stared, rapt, but Berti broke the spell, eager to explore.

‘No Berti,’ Carla whispered.

Nino tapped her arm: ‘There it is.’

Opposite, the pavement widened and a small bar lay at the furthest edge. Carla blinked, wondering if it really existed, as Nino ignored the shuttered front entrance and led them along an overgrown side path. They stopped at the back door.

‘Push top, bottom, then middle,’ Nino reminded himself. The door opened inwards and a torch lay near the entrance.

Nino switched it on to reveal a small windowless room furnished with two wooden chairs and a pile of sacking. There was another door at the far end of the room, a key in its lock. Carla looked from it to her father.

‘It leads to a hallway and the bar,’ Nino explained. ‘We can go there but we can’t use the torch, as the light will show through the shutters. Are you hungry?’

Carla nodded, realising that she was.

‘Alright, come with me.’

Nino unlocked the door and took Carla’s hand. ‘Follow me until your eyes are accustomed to the dark. Berti, wait here.’

The dog sat and Carla left the door ajar. ‘Good boy.’

Nino led her into the bar. He filled a jug with water from the tap and placed it on a tray with a bowl and two glasses. ‘Can you carry it back?’

‘Alright.’ Carla gingerly retraced her steps.

Minutes later, Nino returned with another tray containing a part loaf of bread and a wedge of cheese. ‘Arturo always leaves something, just in case,’ Nino murmured as he divided the food into three portions. Carla guessed that the food had been intended for one, not three.

Carla had eaten half of her portion when she looked up. Nino’s food was untouched and he seemed confused.

‘I thought the elephant moved; I felt the plinth tremble and that’s when I fell.’

Carla nodded: ‘I saw its trunk move. The first time was slight but the second time it flicked from side to side. Maybe it was the torchlight …’

‘Perhaps, or we were being helped. It’s our city, after all …’ Nino suddenly grinned: ‘I hadn’t expected a singing dog’s head. Lovely voice, Berti.’

The dog opened one eye. He had finished his food and was curled up on the floor.

‘Berti’s right. Let’s finish our food and try to sleep. We’ll leave early tomorrow, as soon as the curfew is lifted.’

**************************************************************************

The pile of sacking included two blankets and Nino and Carla arranged their makeshift bedding. Carla was sure that she would not sleep but hours later woke to see Nino watching her as he stroked Berti.

‘The curfew’s over in fifteen minutes and we’ll leave then. If you fold up the bedding, I’ll make something like coffee.’

They cleared away the traces of their stay and left. Outside, it was just becoming light but already the Lungotevere was full of civilians and soldiers. They crossed the road to walk alongside the river.

‘This pavement’s busier, so we’re less likely to stand out,’ Nino explained.

As they approached the Ponte Vecchio, Carla noticed a young man and woman walking towards them. They both seemed surprised to see Nino.

‘Good morning.’ The man smiled.

‘Good morning. Cold, isn’t it?’ Nino replied

The man and woman turned onto the cobbled bridge.

‘You know them?’ Carla whispered.

‘Yes, colleagues.’

When Carla was younger, she had proudly told her friends: ‘Papa’s a violinist, he plays at the Opera House.’ Today, he was holding the violin case, just as she remembered, but how did he spend his days now? She shivered, suddenly afraid, and Berti brushed against her leg as if he understood.

‘Alright?’ Nino squeezed her hand. Carla nodded, wondering if everyone could read her thoughts.

**************************************************************************

One foot in front of the other … I can’t say I’m tired

Carla marvelled that her father’s pace never faltered, as Berti trotted happily alongside.

‘Nearly there,’ Nino murmured.

They rounded the corner and Carla saw the Pyramid and the city walls ahead.

‘The soldiers will check our papers but it’s just routine. Don’t worry if I cough and my voice sounds different: my papers say that I was invalided out of the army with lung damage.’

They joined the small queue.

‘Your papers.’

Nino handed his to the soldier. A minute later, the soldier returned them.

‘Next.’

Carla’s papers were genuine, but her hand shook.

The soldier frowned as he read them: ‘You are not father and daughter?’ He looked from Nino to Carla.

Carla opened her mouth, but Nino was quicker: ‘My niece, my sister’s girl. She’s coming to help her grandmother.’

The soldier nodded and handed Carla her papers.

They hurried away but a second soldier’s voice rang out: ‘Wait!’

They turned, dreading what would follow.

The soldier pointed to the violin case: ‘Open it.’

Nino obliged.

‘It’s yours?’

‘Yes.’

‘Then play a tune – anything you like.’

It had been months but Nino’s fingers were agile and he played with ease.

The soldiers were quick to join in:

Stille Nacht, heilige Nacht …

‘Happy Christmas, Maestro.’

They were free to go: Nino, Carla and Berti.