When the Germans occupied Rome in September 1943, food was scarce. A system of rationing was already in place but food rations were reduced further over the ensuing months. Rations were available only to those who had a Carta Annonaria, or ration card.

Feeding the freedom fighters

From September 1943 until June 1944, groups of partisans were stationed outside of Rome. A combination of former servicemen and other volunteers, they attacked and ambushed the German occupiers, frequently targeting communication and transport lines that led to the front at Monte Cassino.

Within Rome were many resistance groups, and Gap (Gruppi di Azione Patriottica) was one of the most famous. Its members operated in small groups, “cells”, known by their “battle names”. They proved particularly effective at launching attacks against the Germans.

The resistance was not confined to military-style action. Members sourced intelligence, aided fugitives and otherwise used their skills to support the resistance effort. Sympathetic public officials often helped in secret.

Some resistance members lived a double life and remained openly in Rome but healthy men of working age and former servicemen were generally forced into hiding. One of the largest problems for the resistance was how to feed them; their ration cards were cancelled once they failed to present themselves to the Germans for approved work or military service.

Initially, the general population gave them food but, once rations were further reduced, few had food to spare. Sympathetic public officials tried to help although they could only supply around twenty or thirty ration cards at a time, as the cards were jealously guarded by the Germans. The growing numbers who needed them were in the tens of thousands in Rome and in similar numbers outside of the city.

We’ll make our own ration cards

One resistance group decided to make ration cards that would resemble the real ones as closely as possible. The task was entrusted to Ettore Basevi, who led the group’s press and information section. He consulted craftsmen, who all raised one major concern: the real cards were produced with watermarked paper. If forged cards were used regularly, they would be covered with shopkeepers’ stamps and would soon look authentic but, without a watermark, they would not withstand rigorous official scrutiny.

The group tried to obtain watermarked paper from the mill that produced it for the official cards but the Germans kept a close watch and no-one at the mill was able to help. The only other option, the group concluded, was to obtain the paper from the state printworks.

Break-in at the state printworks

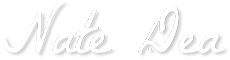

Sympathetic members of the Guardia di Finanza (fiscal police) agreed to help the resistance gain access to the printworks in Piazza Verdi. Initially, a few men entered the workshop to determine the best way to take the paper. They reported back and plans were made.

It was a rainy night, around 2am, when a van stopped in Piazza Verdi in front of a concealed entrance. Basevi and four colleagues got out and quickly entered the printworks, using the doorway that had been left open by the Guardia di Finanza. The Guardia’s men were posted as sentries nearby, pretending not to notice the five men but ready to warn them of danger!

The five spent about half an hour unloading large packages from their van and carrying them into the printworks. Then they brought similar packages out of the printworks, which they deposited in the van.

The packages they took contained the watermarked paper and the ones they carried into the printworks contained paper without watermarks. They hoped that, as the packages looked similar, it would be some time before anyone in the printworks noticed, and that proved to be the case. Once the van was full, the five men left and the entrance closed silently behind them.

Producing the ration cards

Soon afterwards, around five hundred thousand sheets of ration card paper were deposited in a secure place; now the group had the right paper. Helpful contacts in the office responsible for rationing provided a perfect photographic reproduction of a standard ration card. That was turned into a printer’s block by a zincographer who had been imprisoned around twenty times under Mussolini’s fascist regime. Various stamps were also produced, and everything was entrusted to printers who already printed clandestine newssheets for the resistance.

The police raid

Basevi arrived at the printers to make the final arrangements but minutes later the printers received a telephone call. It was a warning in pre-arranged terms and they hurriedly loaded the main components, including paper and stamps, into a van. The van left just as a group of police burst in and carried out a detailed search. The person who had given the timely warning to the printers was a friendly police inspector.

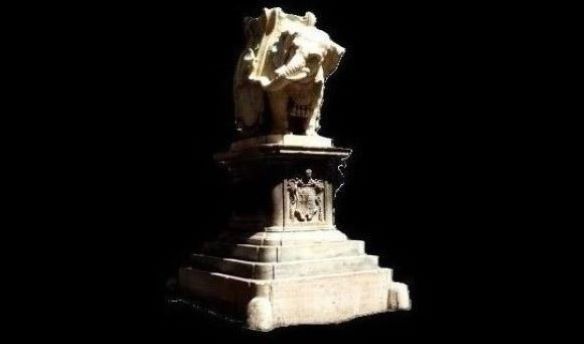

After the van left, Basevi remained at the printers’ premises; it would attract suspicion if he left suddenly and he believed that all of the incriminating items had been taken in the van. In fact, one item had been left behind: the carefully constructed printer’s block. The police officer who picked it up realised what it was and arrested Basevi and the printers. The penalty for having a block for forging ration cards was death but they were saved once more by the police inspector. Somehow, he made the block disappear and with it the proof against them. Basevi and the printers were imprisoned in Regina Coeli prison for forty days but, lacking proof, the police then released them.

Back to work

As soon as he was released, Basevi went back to work on the ration cards, this time with different printers. The mission was accomplished: half a million ration cards were released within Rome, in the surrounding countryside and even some in central Italy. Those used outside of Rome required different stamps for the local region, and the group obtained those as well. The cards were transported with the help, once more, of the Guardia di Finanza.

Who’s eating the food?

Meanwhile, the Germans became concerned by the increase in food consumption. They increased checks on ration cards but those they inspected were perfect. Members of Mussolini’s republican government guessed what had happened. They announced on the radio that false ration cards were in circulation and offered rewards for information, threatening death to those responsible. They learnt nothing.

The Germans considered cancelling all ration cards and issuing new ones with distinguishing features. It might have solved their problem but the Director of the office responsible for ration cards warned that it would require months of intense activity. The project was never commenced and the ration card conundrum was overtaken by events, in particular the liberation of Rome.

The forged ration cards helped feed innumerable members of the resistance and partisans, and they brought a further benefit: anyone with a ration card could use it to confirm the veracity of other identity papers … which in most cases were also forged.

These exploits were first reported shortly after Rome’s liberation in “Roma Sotto Il Terrore Nazista” by Armando Troisio.